Stoicism

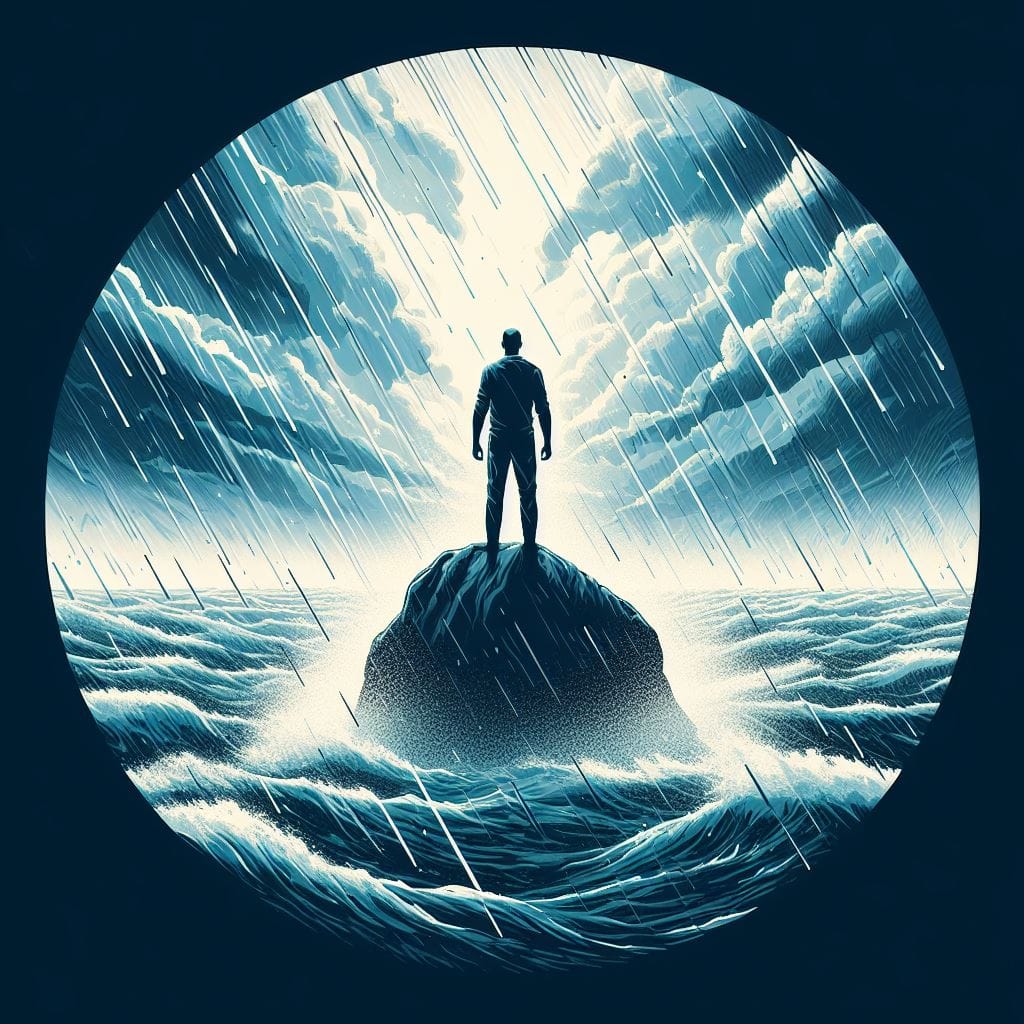

Stoicism offers us a way to live our life in accordince to our values. It asks us to accept that not everything is in our control and for the discipline to master our emotions.

In this post, I’ll discuss Stoicism and where the meme version shortchanges the deeper philosophy, how to think about your values, and practical tips to live a more aligned life.

Stoicism has a curious reputation. There’s the meme version: the person who shows no emotion. That was it for my understanding of Stoicism too. After reading How to Think Like a Roman Emperor by Donald J Robertson, Letters from a Stoic by Seneca, and Discipline is Destiny by Ryan Holiday I’ve come to deeply appreciate Stoicism (as distinct from stoicism–the memed version described earlier).

So what is missing from the simple version? A much deeper life philosophy. How to Think describes it this way: “Being emotionally tough or resilient is just one small part of that philosophy, and lowercase stoicism neglects the entire social dimension of Stoic virtue, which has to do with justice, fairness, and kindness to others.”

Stoicism is very closely related to Cynicism. Note that Cynicism and cynicism are very different. Lower-case cynicism is about doubting everything and general negativity. The philosophical school of upper-case Cynicism shares many of the same thoughts but differs in the approach of adding voluntary hardship to build character. Stoicism, by contrast, accepts that life is difficult but you don’t need to go out of your way to make it harder. Joy is fine too.

The Roman Emperor in Robertson’s book is Marcus Aurelius:

He showed me that there are more important things in life and that true wealth comes from being contented with whatever you have rather than desiring to have more and more

Put much less elegantly, you should optimize for serotonin, not dopamine. Clear Thinking offers a similar life lesson. We see echoes of the answers given by the Stoics.

Philosophy

Before we can think about applying it, we should spend some time to more formally define the philosophy.

There is a key emphasis on the ephemerality of life. Some misfortunes are inevitable. In the long run, material outcomes do not matter as much as what you do with your circumstances. As a result, virtue must be its own reward.

In addition, your feelings and emotions should be thought of as automatic and natural. There should be no judgment attached. However, what you do with those emotions and how you react is the most important part. One outward form this takes is in the pop-culture view of lower-case stoicism, where the stoic doesn’t react. Rather, the stoic should conquer negative reactions and channel them into healthy actions. For example, channeling frustration into industry rather than complaint.

What are some of the principles to guide the correct course of action? Stoicism suggests wisdom, justice, fairness, and kindness amongst others. The deeper point is to find a way to live your life in accordance with your values. Joy will follow from this pursuit, but it’s a trap to directly pursue joy or happiness (this gets you closer to dopamine and further from serotonin). From How to Think:

The Stoic Sage, or wise man, needs nothing but uses everything well; the fool believes himself to “need” countless things, but he uses them all badly.

Seneca argues that the role of a classical education is to “[not that it] can bestow virtue, but because they prepare the soul for the reception of virtue.” And so it should be with how we approach influencing others. But before we can do that, we need to think deeply about just what type of life we want to lead.

Defining Your Own Values

While the previous book review of How Will You Measure Your Life explores a lot of traps with the wrong values, the books here offer a concrete guide to thinking about your own values.

The first, most important step is to spend time in reflection deeply thinking about your values. For example, by asking yourself this set of questions from How to Think:

- What’s ultimately the most important thing in life to you?

- What do you really want your life to stand for or represent?

- What do you want to be remembered for after you’re dead?

- What sort of person do you most want to be in life?

- What sort of character do you want to have?

- What would you want written on your tombstone?

Note: if you want more questions to help you with this, please check the appendix of this post.

I would be surprised if these answers do not evolve as you go through life. That they would change is at the heart of maturing and growing as a person. For me, they have changed the most after I had kids. I’m not comfortable writing all of these answers here. I am comfortable sharing that I do value helping others, including by writing posts like this.

Invest the time. If you don’t know the answer to those questions, it’s even more crucial that you do so. Christensen’s offers a similar insight in How Will You Measure Your Life:

I apply my knowledge of the purpose of my life every day. This is the most valuable, useful piece of knowledge that I have ever gained.

Once you’ve identified these values, you should spend effort to live in accordance with those values.

Practical Tips

So just how do you do that? How do you go about putting Stoicism into practice – so that you are governed by actions you are proud of? Here are some of the practical tips across the three books plus my own observations:

- A morning meditation routine – something I need to be better about putting this into practice. Here’s the template, as outlined by How to Think. In reflection of the day (or week) before, ask yourself: what did you do poorly? When were you ruled by your emotions? What did you do well? How did you do that part? And most importantly, what would you do differently? I have found that after sleeping and letting my brain reorganize my understanding of yesterday, these insights come more clearly.

- Cognitive distancing – you may be caught up in a maelstrom of emotion. Stoics refer to a technique as getting a “bird’s eye view” or removing (and observing) yourself in that situation. I’m reminded of Clear Thinking’s suggestion of having your (simulated) personal board of directors and wondering what they would say, if they were watching you. Anything that gives you an outside perspective reinforces this gap between emotion and action. In general, “imagining that you’re being observed” is a powerful method for improvement. For me, this has been the most powerful part of meditation: the distancing of thought from action.

- Habits and gaps – revisit your habits. What is serving you well? What isn’t? For example, how much time do you spend on social media? I’d argue that the hardest bad habits are actually the mildly good ones. They offer some value and are pleasurable, so they’re very easy to rationalize. For me the hardest was my Google Discover feed on my phone which I had to shut off. I spent a lot of time there and got only mild benefit. When I did my own time audit, I also found that notifications were a big distraction away from intentionality, so now my phone is always in DND. There’s a lot more to be written about the cultivation of new habits (Atomic Habits, Power of Habit, all in a future blog post!) but you first need room for them by removing the bad habits.

- Activity and agency – move with purpose and energy towards your goals. Don’t wait for things to happen to you. Cate Hall has a fascinating substack post on this idea. Similarly, in Discipline: “You can choose the means, but the method is a must: You must be active.” This is reinforced by the point that showing up is a must. Show up to the things that matter and put your energy there. If you find yourself energy limited, I encourage you to revisit the foundations of your health.

- Discipline. Similar to those devious, mildly-good habits, you’ll need the discipline to say no to many things in order to pursue the highest virtues and meaningfully progress. This is perhaps best captured by this quote from Discipline: “We joke about the absentminded professor, as if they’re somehow less together than normal people. It’s actually the exact opposite. They are showing us what full commitment looks like in practice. The rest of us are far too concerned with things that don’t matter to recognize that true mental discipline comes at a cost—and they are the ones willing to pay it.” The hardest part of this is learning to say no to many good opportunities.

- Tolerance with others, strictness with yourself. In order to do this with grace, avoid being strict with others. When people are ready to receive a message, they will be receptive. If you try to force something onto them they will resist. The only person you’re allowed to be truly strict with is yourself. As Discipline notes, this will not be easy because there’s a very human temptation to be righteous. This is about understanding that not everyone is on the same journey as you, nor heading to the same destination. It is how you can best express kindness.

Living the best version of your life is hard. For it to be the best version, you will need to work at it. I think it takes more energy to avoid the convenience and ease that modern technology offers. But I can’t think of anything more important to do.

Additional resources:

- How to Think Like a Roman Emperor by Donald J Robertson

- Letters from a Stoic by Seneca

- Discipline is Destiny by Ryan Holiday

I also asked Claude 3 Opus for additional values reflection questions, and got this fantastic list:

- What brings you the greatest sense of fulfillment and meaning?

- What are the non-negotiable principles or values that guide your decisions and actions?

- If you could change one thing about the world, what would it be?

- Who are the people you admire most and what qualities do they embody?

- What experiences or relationships have shaped your values and priorities in life?

- If you had one year left to live, how would you spend your time?

- What legacy do you want to leave for future generations?

- In what ways do you want to make a positive impact on others' lives?

- What would you be willing to sacrifice or struggle for in order to stay true to your deepest values?

- What does a life well-lived look like to you?