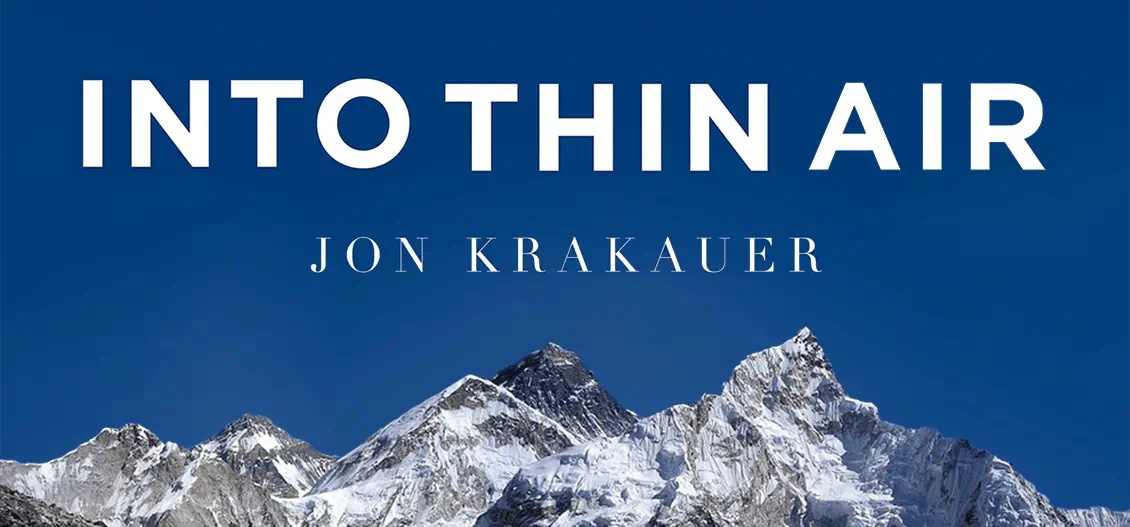

Book Review: Into Thin Air

Climbing Mt Everest is an ordeal. Krakauer documents one of the deadliest climbs and what happened in May of 1996. A fascinating read that tells you about humanity along the way.

There were many, many fine reasons not to go, but attempting to climb Everest is an intrinsically irrational act—a triumph of desire over sensibility.

Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air is a classic. It’s about his experience, as a journalist, during the 1996 Mount Everest climbing season. The book is a rare non-fiction that reads better than most fiction. In the rest of this post I’ll explore just what made this story so exceptional.

His role was as a magazine contributor seeded in one of the top expedition groups of the era, to report on the commercialization of climbing Everest (and to promote that specific tour group).

Up

One of the outstanding elements of the book is the main character, the mountain. Mount Everest is the tallest mountain on earth at 29032 feet above sea level (and climbing–the image is a bit out of date!). Humans do not function at that height. There is literally not enough oxygen for full brain function.

The mountain itself seems to have a mystical hold on people:

As it happened, Tibetans who lived to the north of the great mountain already had a more mellifluous name for it, Jomolungma, which translates to “goddess, mother of the world,” and Nepalis who resided to the south reportedly called the peak Deva-dhunga, “Seat of God.”

To me it seems much more than just a simple mountain, or even the biggest of an otherwise ordinary bunch. There’s something special about it.

There is also not a clear, rational explanation for the desire to climb Everest. In fact, I think that’s what makes it so compelling–the question of why. Why do people risk so much? Why do people find themselves obsessed with this goal?

There has to be some component of longing and searching for meaning:

Above the comforts of Base Camp, the expedition in fact became an almost Calvinistic undertaking. The ratio of misery to pleasure was greater by an order of magnitude than any other mountain I’d been on; I quickly came to understand that climbing Everest was primarily about enduring pain. And in subjecting ourselves to week after week of toil, tedium, and suffering, it struck me that most of us were probably seeking, above all else, something like a state of grace.

There’s also an element of status (and I’m reminded of the movie Free Solo):

Getting to the top of any given mountain was considered much less important than how one got there: prestige was earned by tackling the most unforgiving routes with minimal equipment, in the boldest style imaginable. Nobody was admired more than so-called free soloists: visionaries who ascended alone, without rope or hardware.

And lastly, determination:

Unfortunately, the sort of individual who is programmed to ignore personal distress and keep pushing for the top is frequently programmed to disregard signs of grave and imminent danger as well. This forms the nub of a dilemma that every Everest climber eventually comes up against: in order to succeed you must be exceedingly driven, but if you’re too driven you’re likely to die. Above 26,000 feet, moreover, the line between appropriate zeal and reckless summit fever becomes grievously thin. Thus the slopes of Everest are littered with corpses.

I can’t help but conclude that there’s some relationship between this type of ambitious, determined striving and our progress as a species (see dopamine).

Down

This story is also a tragedy. Of the 6 climbers including Krakauer who made the summit, only 2 survived. Many others lost their lives on the mountain that year. The way to climb Everest, as I understand it, is to acclimate to high altitude and make your way up the various camps. Starting at base camp (18000 feet elevation) and through camps 1-4. Camp 4, at 26000 feet, is in the so-called “death zone” since that elevation cannot support human life for extended durations. If you are going to summit Everest, you basically go to camp 4 and then, when the time is right, try a straight shot to the summit and back on a clear May day. Krakauer observed:

Although in a few hours we would leave camp as a group, we would ascend as individuals, linked to one another by neither rope nor any deep sense of loyalty. Each client was in it for himself or herself, pretty much.

Like the rest of the climb, the book details the steps involved including just how physically taxing such an event would be. About summiting, he offers:

Reaching the top of Everest is supposed to trigger a surge of intense elation; against long odds, after all, I had just attained a goal I’d coveted since childhood. But the summit was really only the halfway point. Any impulse I might have felt toward self-congratulation was extinguished by overwhelming apprehension about the long, dangerous descent that lay ahead.

Krakauer makes it back to camp 4 alone, and not in great shape. When he left the summit, his tour guide Rob Hall was still waiting for the rest of the group to make it up there. I think it was the last time he saw Rob and many other co-summiteers alive.

Krakauer spends part of the book reflecting and dealing with survivor’s guilt. Rob had insisted on discipline, especially a strict turn-around time on summit day. In practice they went way past the designated cutoff, leading to tragedy as a storm came in on the stragglers:

Certainly time had as much to do with the tragedy as the weather, and ignoring the clock can’t be passed off as an act of God. Delays at the fixed lines were foreseeable and eminently preventable. Predetermined turn-around times were egregiously ignored.

This reminds me of thinking about system failures, especially the book Command and Control by Eric Schlosser, where failure has many proximate causes. In the case of Command it concerned nuclear weapons storage in the United States. All of your sequential safety checks will fail due to some seemingly minor reason initially. In retrospect there will be many signs that not all was alright. The most difficult part of it all is to have the discipline to stay true to those warnings even when they are not always strictly necessary.

In summary, Into Thin Air, is an excellent chronicle of climbing Everest that had the unfortunate privilege of being during one of the deadlier seasons. It’s an amazing book at giving you a very faint sense of what climbing Everest might be like and how many reasonable decisions can actually lead to tragedy. What makes it exceptional is how it touches on so many deeper human emotions and experiences. After reading it, it’s clear why it remains so high on many must-read lists.

Additional Quotes:

Walking to the mess tent at mealtime left me wheezing for several minutes. If I sat up too quickly, my head reeled and vertigo set in. The deep, rasping cough I’d developed in Lobuje worsened day by day. Sleep became elusive, a common symptom of minor altitude illness. Most nights I’d wake up three or four times gasping for breath, feeling like I was suffocating. Cuts and scrapes refused to heal. My appetite vanished and my digestive system, which required abundant oxygen to metabolize food, failed to make use of much of what I forced myself to eat; instead my body began consuming itself for sustenance.

If the Icefall required few orthodox climbing techniques, it demanded a whole new repertoire of skills in their stead—for instance, the ability to tiptoe in mountaineering boots and crampons across three wobbly ladders lashed end to end, bridging a sphincter-clenching chasm. There were many such crossings, and I never got used to them.

In fact, the gale of May 10, though violent, was nothing extraordinary; it was a fairly typical Everest squall. If it had hit two hours later, it’s likely that nobody would have died. Conversely, if it had arrived even one hour earlier, the storm could easily have killed eighteen or twenty climbers—me among them.

Additional resources:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3cUgJLvToA gives you a sense of the climb (and the crowds!)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khumbu_Icefall

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Everest