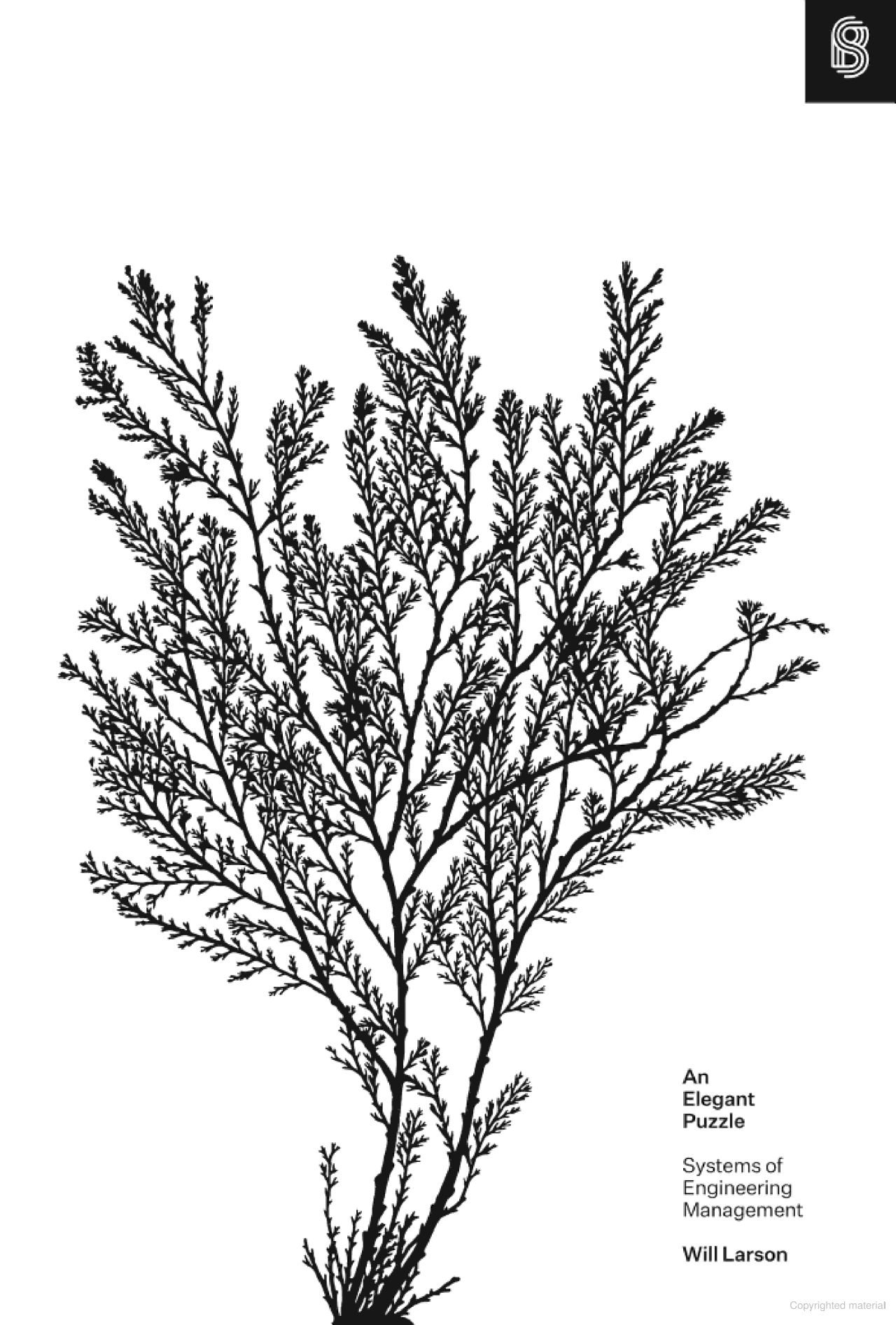

Book Review: An Elegant Puzzle

Will Larson's An Elegant Puzzle gives us a lot of great advice on how to be an effective engineering manager. Pragmatism is a theme, as are small team sizes.

“The worst theory of management is to not have one at all, but the second worst is one that doesn’t change.”

Will Larson’s An Elegant Puzzle advocates strongly for having a theory of management that is flexible and adaptable. He wrote this book as an engineering leader at Stripe (and is now the CTO at Carta). One of his strong suggestions regards team size: 6 to 8. For managers of managers: 4 to 6. Outside of these bounds you run into issues. At this size, you can devote time to active coaching, coordination, and leading the mission. Above 8 or 9 the manager becomes more of a reactive coach.

For growth, Larson advocates adding people in batches where possible, so that ramp-up can be better coordinated. Drip-feeding is much more disruptive to a team’s ability to gel. Additionally, once you have a high performing team, shuffling them likely leads to a loss of that high productivity, even if all the members are retained. Shifting scope is more effective than shifting people.

The idea of “slack” in a team – surplus capacity – can lead to better overall velocity as they can fix existing issues and innovate more.

When trying to run a team efficiently, Larson introduces the concept of time thieves. The top one is hiring–from interviews to training this can be significant if your org is growing quickly. The next is Slack messages, pings in other forms, alerts, mass emails and so on. Can you funnel them? Ad hoc meetings are another big one. To address, block significant chunks of time. Small companies with great documentation have managed to avoid this, but it’s very hard (impossible?) to achieve at a larger scale.

Larson is a very strong advocate for the idea of thinking systems (for which he recommends Thinking in Systems by Donella Meadows). The main idea is that many things are related, and very little happens in a vacuum. A related idea from Lessons from the Titans is that some of the best companies rigorously benchmark. Combining the two will allow you to deeply understand the productivity of your organization and where gaps may lie. With this you can think of the repetitive cycle of problem discovery, selection, validation, and execution.

In An Elegant Puzzle, strategy documents are grounded to a specific challenge. Vision documents are aspirational and allow different teams to coordinate. You’ll want as few of the latter as possible. Success here is when people independently decide something by referring to your vision. The opposite is when people are at odds with it.

Metrics are an important lever for both goal settings and guiding an organization. Teams should know where they are both in absolute terms as well as relative to the rest of the org. Done well, these can nudge or encourage the key behaviors you want to reinforce. Done poorly and you have confusion and low velocity.

Regarding reorgs, the book strongly advocates using them for solving structural problems but avoiding them if it’s mainly to solve a people management issue (a broken relationship especially). At a start-up, getting the reorg right is one of the key things you’ll need to do well.

In a brief aside on career advice–think about skills, not external levels like promotion:

Chasing the next promotion is at best a marker on a mass-produced treasure map, with every shovel and metal detector re-covering the same patch. Don’t go there. Go somewhere that’s disproportionately valuable to you because of who you are and what you want.

In the current business environment, this advice seems better than ever. My recommendation would be to think deeply about what you’re good at and where you want to be adding more value. Then try to find ways to get even better at it. Audit your time to figure out where it is going. Are you spending time on the areas where you can add the most value?

For growth, try to build communities of learning. Larson recommends that this include: anchoring on discussions, using small break-out groups, sharing learnings, and choosing topics something the group knows about so they can build off of it.

As you grow as a leader, the most important activity you will undertake is being able to say no. This involves articulating your team’s constraints and resources, and what best supports them in the long run.

Larson’s theory of management:

- The Golden Rule makes sense

- Give everyone explicit ownership

- Reward should follow from the completion of the work

- Lead from the front

- Strong relationships > any problem

- People over process

- Do the hard things now

- Do what’s right for company, team, self in that order

- Think for yourself

If you want more details, I recommend understanding the additional context the full book provides. While there are a lot of items on this list, they give you a good starting point for any situation. The theme is to be flexible, invest in people, and don’t shy away from the difficult.

In section 4.5, there’s a long list of where managers can get stuck, especially early in their career. I think the best managers learn from the mistakes of others, and can at least spend less time getting stuck. A very important one is to manage up effectively. Relatedly, if you want your manager team to treat each other as a “first team,” it’s very important for the leader to be a strong referee. For reference, here are the items that stood out to me:

- Only managing down: building something the team wants but the company and customers are not interested in.

- Not managing up: sharing the good work your team is doing upwards and understanding the landscape and priorities

- Defining the role too narrowly: in the end, the team needs to get things done and the manager needs to fill all the gaps

In thinking about your career, think about transitions–when your work changed meaningfully–and reflect on what it was that got you through it. Growth comes from change. You bear some responsibility for this in your own career.

There is a lot more in this helpful guide, which I recommend for anyone interested in growing as an engineering manager.

Here are some quotes that stood out to me:

I’ve sponsored quite a few teams of one or two people, and each time I’ve regretted it. To repeat: I have regretted it every single time. An important property of teams is that they abstract the complexities of the individuals that compose them.

The fixed cost of creating and maintaining a policy is high enough that I generally don’t recommend writing policies that do little to constrain behavior. In fact, that’s a useful definition of bad policy. In such cases, I instead recommend writing norms, which provide nonbinding recommendations.

“With the right people, any process works, and with the wrong people, no process works.”